Circumstances:

Transair flight 810, a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121 cargo flight, experienced a partial loss of power involving the right engine shortly after takeoff and a water ditching in the

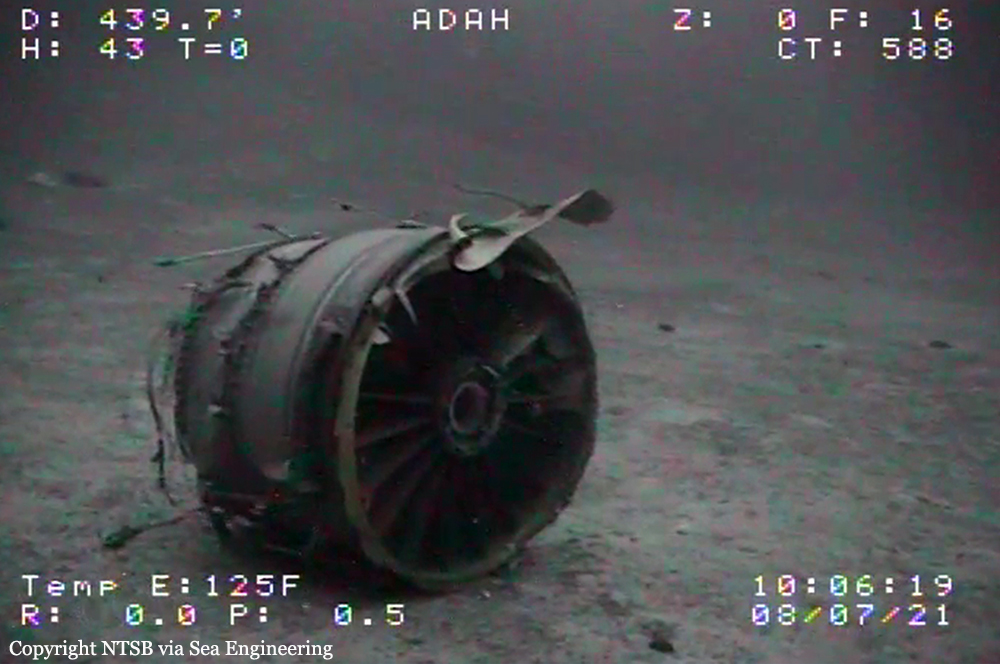

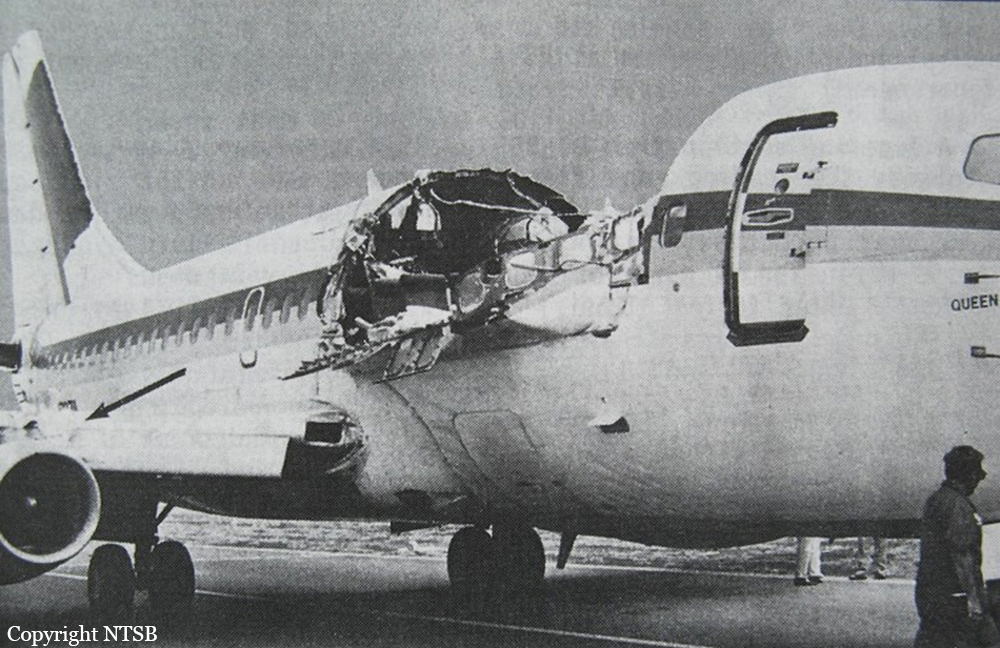

Pacific Ocean about 11.5 minutes later. This analysis summarizes the accident and evaluates (1) the right engine partial loss of power, (2) the captain's communications with air traffic control (ATC) and the first officer's left and right engine thrust reductions, (3) the first officer's misidentification of the affected engine and the captain's failure to verify the information, (4) checklist performance, and (5) survival factors. Maintenance was not a factor in this accident. The flight data recorder (FDR) showed that, when the initial thrust was set for takeoff, the engine pressure ratios (EPR) for the left and right engines were 2.00 and 1.97, respectively. Shortly after rotation, the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recorded a “thud” and the sound of a low-frequency vibration. The captain (the pilot monitoring at the time) and the first officer (the pilot flying) reported that they heard a “whoosh” and a “pop,” respectively, at that time. As the airplane climbed through an altitude of about 390 ft while at an airspeed of 155 knots, the right EPR decreased to 1.43 during a 2-second period. The airplane then yawed to the right; the first officer countered the yaw with appropriate left rudder pedal inputs. The CVR showed that the captain and the first officer correctly determined that the No. 2 (right) engine had lost thrust within 5 seconds of hearing the thud sound. After moving the flaps to the UP position, the captain reduced thrust to maximum continuous thrust, causing the left EPR to decrease from 1.96 to 1.91 while the airplane was in a climb. (The right EPR remained at 1.43). The captain reported that he did not move the thrust levers again until after he became the pilot flying. The first officer stated that, after the airplane leveled off at an altitude of about 2,000 ft, he reduced thrust on both engines. FDR data showed that thrust was incrementally reduced to near flight idle (1.05 EPR on the left engine and then 1.09 EPR on the right engine) and that airspeed decreased from about 250 to 210 knots. (A decrease in airspeed to 210 knots was consistent with the operator’s simulator guide procedures for a single-engine failure after the takeoff decision speed [V1]. The simulator guide, which supplemented information in the company’s flight crew training manual, contained the most recent operator guidance for single-engine failure training at the time of the accident.) The captain was unaware of the first officer’s thrust changes because he was busy contacting the controller about the emergency. The captain told the controller, “we’ve lost an engine,” but he had declared the emergency to the controller twice before this point, as discussed later in this analysis. The captain instructed the first officer to maintain a target speed of 220 knots (which the captain thought would be “easy on the running engine”), a target altitude of 2,000 ft, and a target heading of 240°. (About 52 seconds earlier, the controller had issued the 240° heading instruction to another airplane on the same radio frequency.) About 3 minutes 14 seconds after the right engine loss of thrust occurred, the captain assumed control of the airplane; at that time, the airplane’s airspeed was 224 knots and heading was 242°, but the airplane’s altitude had decreased from about 2,100 ft (the maximum altitude that the airplane reached during the flight) to 1,690 ft. The captain increased the airplane’s pitch to 9°; the airplane’s altitude then increased to 1,878 ft, but the airspeed decreased to 196 knots. The captain subsequently stated, “let’s see what is the problem...which one...what's going on with the gauges,” and “who has the E-G-T [exhaust gas temperature]?” The first officer stated that the left engine was “gone” and “so we have number two” (the right engine), thus misidentifying the affected engine. The captain accepted the first officer’s assessment and did not take action to verify the information. Afterward, the EPR level on the right engine began to increase in response to the captain advancing the right thrust lever so that the airplane could maintain airspeed and altitude. Right EPR increased and decreased several times during the rest of the flight (coinciding with crew comments regarding the EGT on the right engine and low airspeed) while the left EPR remained near flight idle. The first officer asked the captain if they “should head back toward the airport” before the airplane traveled “too far away,” and the captain responded that the airplane would stay within 15 miles of the airport. During a postaccident interview, the captain stated that, because there was no fire and an engine “was running,” he intended to have the airplane climb to 2,000 ft and stay within 15 miles of the airport to avoid traffic and have time to address the engine issue. The captain also stated that he had been criticized by the company chief pilot for returning to the airport without completing the required abnormal checklist for a previous in-flight emergency. Although the captain’s decision resulted in the accident airplane flying farther away from the airport and farther over the ocean at night, the captain’s decision was reasonable for a single-engine failure event. The captain directed the first officer to begin the Engine Failure or Shutdown checklist and stated that he would continue handling the radios. The first officer began to read aloud the conditions for executing the Engine Failure or Shutdown checklist but then stopped to tell the captain that the right EGT was at the “red line” and that thrust should be reduced on the right engine. The captain then decided that the airplane should return to the airport and contacted the controller to request vectors. The flight crew continued to express concern about the right engine. The first officer stated, “just have to watch this though…the number two.” The captain asked the first officer to check the EGT for the right engine, and the first officer responded that it was “beyond max.” Afterward, the captain told the first officer to continue with the Engine Failure or Shutdown checklist and finish as much as possible. The first officer resumed reading aloud the conditions for performing the checklist but then stopped to state, “we have to fly the airplane though,” because the airplane was continuing to lose altitude and airspeed. The captain replied “okay.” As a result, the flight crew did not perform key steps of the checklist, including identifying, confirming, and shutting down the affected (right) engine. The first officer told the captain that the airplane was losing altitude; at that time, the airplane’s altitude was 592 ft, and its airspeed was 160 knots. The captain agreed to select flaps 1 (which the first officer had previously suggested likely because the airplane was slowing). The CVR then recorded the first enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS) annunciation (500 ft above ground level); various EGPWS callouts and alerts continued to be annunciated through the remainder of the flight. The captain then told the controller that “we’ve lost number one [left] engine…there’s a chance we’re gonna lose the other engine too it’s running very hot….we’re pretty low on the speed it doesn't look good out here.” Also, the captain mentioned that the controller should notify the US Coast Guard (USCG) because he was anticipating a water ditching in the Pacific Ocean. Because of the high temperature readings on the right engine, the flight crew thought, at this point in the flight, that a dual-engine failure was imminent. During a postaccident interview, the captain stated that his priority at that time was figuring out how the airplane could stay in the air and return safely to the airport. The captain also stated that he attempted to resolve the airplane’s deteriorating energy state by advancing the right engine thrust lever. However, with the left engine remaining near flight idle, the right engine was not producing sufficient thrust to enable the airplane to maintain altitude or climb. The captain’s communication with the controller continued, and the first officer stated, “fly the airplane please.” The controller asked if the airport was in sight, and the captain then asked the first officer whether he could see the airport. The first officer responded “pull up we’re low” to the captain and “negative” to the controller; the captain was likely unable to respond to the controller because he was trying to control the airplane. The captain asked the first officer about the EGT for the right engine; the first officer replied “hot…way over.” The captain then asked about, and the controller responded by providing, the location of the closest airport. Afterward, the CVR recorded a sound similar to the stick shaker, which continued intermittently through the rest of the flight. The CVR then recorded sounds consistent with water impact. The airplane came down into the Pacific Ocean about two miles offshore and sank. Both crew members were rescued, one was slightly injured and a second was seriously injured. The wreckage was later recovered for investigation purposes.