Country

Crash of a Beechcraft B200 Super King Air in Akureyri: 2 killed

Date & Time:

Aug 5, 2013 at 1329 LT

Registration:

TF-MYX

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Reykjavik - Akureyri

MSN:

BB-1136

YOM:

1983

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

1

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

2

Captain / Total hours on type:

1700.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

1100

Aircraft flight hours:

15247

Aircraft flight cycles:

18574

Circumstances:

On 4th of August 2013 the air ambulance operator Mýflug, received a request for an ambulance flight from Höfn (BIHN) to Reykjavík Airport (BIRK). This was a F4 priority request and the operator, in co-operation with the emergency services, planned the flight the next morning. The plan was for the flight crew and the paramedic to meet at the airport at 09:30 AM on the 5th of August. A flight plan was filed from Akureyri (BIAR) to BIHN (positioning flight), then from BIHN to BIRK (ambulance flight) and from BIRK back to BIAR (positioning flight). The planned departure from BIAR was at 10:20. The flight crew consisted of a commander and a co-pilot. In addition to the flight crew was a paramedic, who was listed as a passenger. Around 09:50 on the 5th of August, the flight crew and the paramedic met at the operator’s home base at BIAR. The flight crew prepared the flight and performed a standard pre-flight inspection. There were no findings to the aircraft during the pre-flight inspection. The pre-flight inspection was finished at approximately 10:10. The departure from BIAR was at 10:21 and the flight to BIHN was uneventful. The aircraft landed at BIHN at 11:01. The commander was the pilot flying from BIAR to BIHN. The operator’s common procedure is that the commander and the co-pilot switch every other flight, as the pilot flying. The co-pilot was the pilot flying from BIHN to BIRK and the commander was the pilot flying from BIRK to BIAR, i.e. during the accident flight. The aircraft departed BIHN at 11:18, for the ambulance flight and landed at BIRK at 12:12. At BIRK the aircraft was refueled and departed at 12:44. According to flight radar, the flight from BIRK to BIAR was flown at FL 170. Figure 4 shows the radar track of the aircraft as recorded by Reykjavík Control. There is no radar coverage by Reykjavík Control below 5000 feet, in the area around BIAR. During cruise, the flight crew discussed the commander’s wish to deviate from the planned route to BIAR, in order to fly over a racetrack area near the airport. At the racetrack, a race was about to start at that time. The commander had planned to visit the racetrack area after landing. The aircraft approached BIAR from the south and at 10.5 DME the flight crew cancelled IFR. When passing KN locator (KRISTNES), see Figure 6, the flight crew made a request to BIAR tower to overfly the town of Akureyri, before landing. The request was approved by the tower and the flight crew was informed that a Fokker 50 was ready for departure on RWY 01. The flight crew of TF-MYX responded and informed that they would keep west of the airfield. After passing KN, the altitude was approximately 800’ (MSL), according to the co-pilot’s statement. The co-pilot mentioned to the commander that they were a bit low and recommended a higher altitude. The altitude was then momentarily increased to 1000’. When approaching the racetrack area, the aircraft entered a steep left turn. During the turn, the altitude dropped until the aircraft hit the racetrack.

Probable cause:

The commander was familiar with the racetrack where a race event was going on and he wanted to perform a flyby over the area. The flyby was made at a low altitude. When approaching the racetrack area, the aircraft’s calculated track indicated that the commander’s intention of the flyby was to line up with the racetrack. In order to do that, the commander turned the aircraft to such a bank angle that it was not possible for the aircraft to maintain altitude. The ITSB believes that during the turn, the commander most probably pulled back on the controls instead of levelling the wings. This caused the aircraft to enter a spiral down and increased the loss of altitude. The investigation revealed that the manoeuvre was insufficiently planned and outside the scope of the operator manuals and handbooks. The low-pass was made at such a low altitude and steep bank that a correction was not possible in due time and the aircraft collided with the racetrack. The ITSB believes that human factor played a major role in this accident. Inadequate collaboration and planning of the flyover amongst the flight crew indicates a failure of CRM. This made the flight crew less able to make timely corrections. The commander’s focus was most likely on lining up with the racetrack, resulting in misjudging the approach for the low pass and performing an overly steep turn. The overly steep turn caused the aircraft to lose altitude and collide with the ground. The co-pilot was unable to effectively monitor the flyover/low-pass and react because of failure in CRM i.e. insufficient planning and communication. A contributing factor is considered to be that the flight path of the aircraft was made further west of the airfield, due to traffic, resulting in a steeper turn. The investigation revealed that flight crews were known to deviate occasionally from flight plans.

Causal factors:

- A breakdown in CRM occurred.

- A steep bank angle was needed to line up with the racetrack.

- The discussed flyby was executed as a low pass.

- The maximum calculated bank angle during last phase of flight was 72.9°, which is outside the aircraft manoeuvring limit.

- ITSB believes that the commander’s focus on a flyby that he had not planned thoroughly resulted in a low-pass with a steep bank, causing the aircraft to lose altitude and collide with the ground.

Contributory factors:

- The commander’s attention to the activity at the race club area, and his association with the club was most probably a source of distraction for him and most likely motivated him to execute an unsafe maneuver.

- Deviations from normal procedures were seen to be acceptable by some flight crews.

- A flyby was discussed between the pilots but not planned in details.

- The flight crew reacted to the departing traffic from BIAR by bringing their flight path further west of the airport.

- The approach to the low pass was misjudged.

- The steep turn was most probably made due to the commander’s intention to line up with the race track.

Causal factors:

- A breakdown in CRM occurred.

- A steep bank angle was needed to line up with the racetrack.

- The discussed flyby was executed as a low pass.

- The maximum calculated bank angle during last phase of flight was 72.9°, which is outside the aircraft manoeuvring limit.

- ITSB believes that the commander’s focus on a flyby that he had not planned thoroughly resulted in a low-pass with a steep bank, causing the aircraft to lose altitude and collide with the ground.

Contributory factors:

- The commander’s attention to the activity at the race club area, and his association with the club was most probably a source of distraction for him and most likely motivated him to execute an unsafe maneuver.

- Deviations from normal procedures were seen to be acceptable by some flight crews.

- A flyby was discussed between the pilots but not planned in details.

- The flight crew reacted to the departing traffic from BIAR by bringing their flight path further west of the airport.

- The approach to the low pass was misjudged.

- The steep turn was most probably made due to the commander’s intention to line up with the race track.

Final Report:

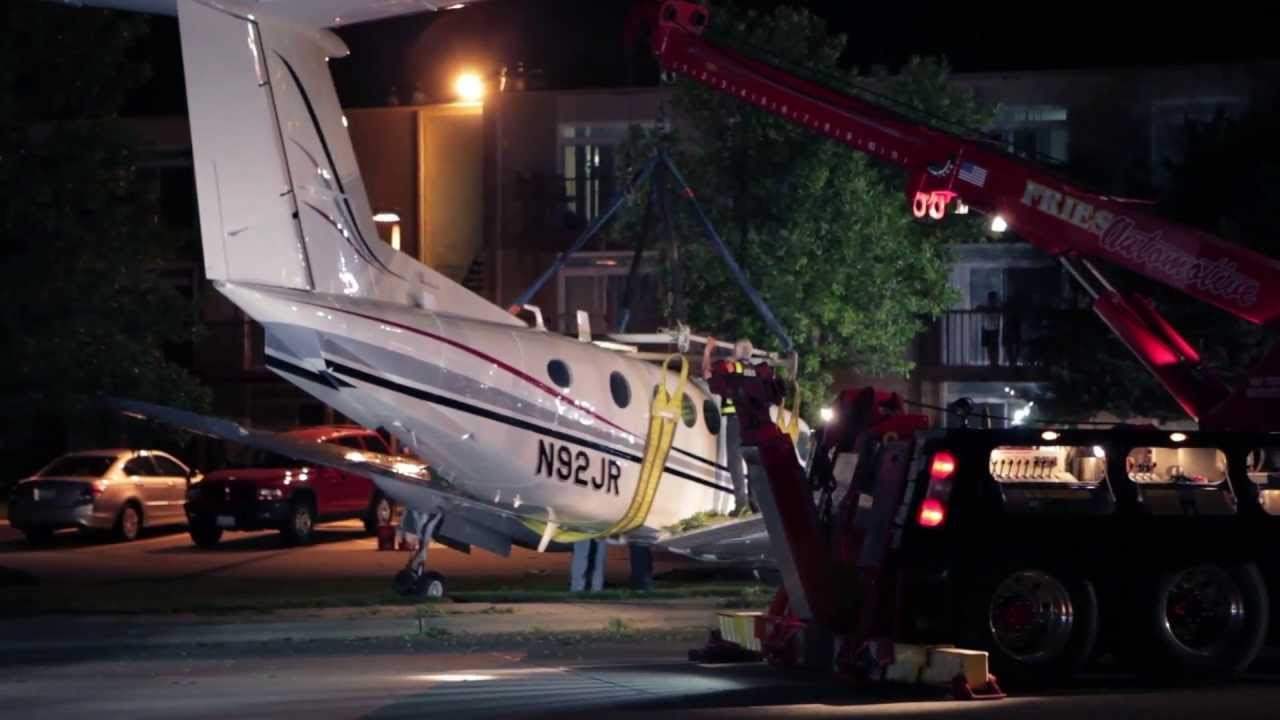

Crash of a Beechcraft 200 Super King Air in Palwaukee

Date & Time:

Jun 25, 2013 at 2030 LT

Registration:

N92JR

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Springfield - Palwaukee

MSN:

BB-751

YOM:

1981

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

572.00

Aircraft flight hours:

6709

Circumstances:

Before departure, the pilot performed fuel calculations and determined that he had enough fuel to fly to the intended destination. While enroute the pilot flew around thunderstorms. On arrival at his destination, the pilot executed the instrument landing system approach for runway 16. While on short final the right engine experienced a total loss of power. The pilot switched the fuel flow from the right tank to the left tank. The left engine then experienced a total loss of power and the pilot made an emergency landing on a road. The airplane received substantial damage to the wings and fuselage when it struck a tree. A postaccident examination revealed only a few gallons of unusable fuel in the left fuel tank. The right fuel tank was breached during the accident sequence but no fuel smell was noticed. The pilot performed another fuel calculation after the accident and determined that there were actually 170 gallons of fuel onboard, not 230 gallons like he originally figured. He reported no preaccident mechanical malfunctions that would have precluded normal operation and determined that he exhausted his entire fuel supply.

Probable cause:

The pilot's improper fuel planning and management, which resulted in a loss of engine power due to fuel exhaustion.

Final Report:

Crash of a Beechcraft B200GT Super King Air in Baker: 1 killed

Date & Time:

Jun 7, 2013 at 1310 LT

Registration:

N510LD

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Baton Rouge - McComb

MSN:

BY-24

YOM:

2007

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

1

Captain / Total hours on type:

5200.00

Aircraft flight hours:

974

Circumstances:

The accident pilot and two passengers had just completed a ferry flight on the recently purchased airplane. A review of the airplane’s cockpit voice recorder audio information revealed that, during the ferry flight, one of the passengers, who was also a pilot, was pointing out features of the new airplane, including the avionics suite, to the accident pilot. The pilot had previously flown another similar model airplane, but it was slightly older and had a different avionics package; the new airplane’s avionics and flight management system were new to the pilot. After completing the ferry flight and dropping off the passengers, the pilot departed for a short cross-country flight in the airplane. According to air traffic control recordings, shortly after takeoff, an air traffic controller assigned the pilot a heading and altitude. The pilot acknowledged the transmission and indicated that he would turn to a 045 heading. The radio transmission sounded routine, and no concern was noted in the pilot’s voice. However, an audio tone consistent with the airplane’s stall warning horn was heard in the background of the pilot’s radio transmission. The pilot then made a radio transmission stating that he was going to crash. The audio tone was again heard in the background, and distress was noted in the pilot’s voice. The airplane impacted homes in a residential neighborhood; a postcrash fire ensued. A review of radar data revealed that the airplane made a climbing right turn after departure and then slowed and descended. The final radar return showed the airplane at a ground speed of 102 knots and an altitude of 400 feet. Examination of the engines and propellers indicated that the engines were rotating at the time of impact; however, the amount of power the engines were producing could not be determined. The examination of the airplane did not reveal any abnormalities that would have precluded normal operation. It is likely that the accident pilot failed to maintain adequate airspeed during departure, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and subsequent impact with terrain, and that his lack of specific knowledge of the airplane’s avionics contributed to the accident.

Probable cause:

The pilot’s failure to maintain adequate airspeed during departure, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and subsequent impact with terrain. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s lack of specific knowledge of the airplane’s avionics.

Final Report:

Crash of a Beechcraft B200 Super King Air in Pias: 9 killed

Date & Time:

Mar 6, 2013 at 0741 LT

Registration:

OB-1992-P

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Lima - Pias

MSN:

BB-1682

YOM:

1999

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

7

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

9

Captain / Total hours on type:

312.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

425

Aircraft flight hours:

3859

Aircraft flight cycles:

4318

Circumstances:

The twin engine aircraft departed Lima-Jorge Chávez Airport at 0625LT on a charter flight to Pias, carrying two pilots and seven employees of the Peruvian company MARSA (Minera Aurífera Retamas) en route to Pias gold mine. On approach to Pias Airport, the crew encountered limited visibility due to foggy conditions. Heading 320° on approach, the crew descended too low when the aircraft collided with power cables, stalled and crashed on the slope of a mountain located 4,5 km from the airport, bursting into flames. The aircraft was destroyed by impact forces and a post crash fire and all 9 occupants were killed.

Probable cause:

Loss of control following the collision with high power cables after the crew lost visual references during an approach completed in poor weather conditions. The following contributing factors were identified:

- Inadequate meteorological information provided by the Pias Airport flight coordinator that did not reflect the actual weather condition in the area,

- Lack of a procedure card to carry out the descent, approach, landing and takeoff at Pias Airport, considering the visual and operational meteorological limitations in the area,

- The copilot training was limited and did not allow the crew to develop skills for an effective CRM in normal and emergency procedures.

- Inadequate meteorological information provided by the Pias Airport flight coordinator that did not reflect the actual weather condition in the area,

- Lack of a procedure card to carry out the descent, approach, landing and takeoff at Pias Airport, considering the visual and operational meteorological limitations in the area,

- The copilot training was limited and did not allow the crew to develop skills for an effective CRM in normal and emergency procedures.

Final Report:

Crash of a Beechcraft B200 Super King Air in Juiz de Fora: 8 killed

Date & Time:

Jul 28, 2012 at 0745 LT

Registration:

PR-DOC

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Belo Horizonte - Juiz de Fora

MSN:

BY-51

YOM:

2009

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

6

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

8

Captain / Total hours on type:

2170.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

415

Aircraft flight hours:

385

Aircraft flight cycles:

305

Circumstances:

The twin engine aircraft departed Belo Horizonte-Pampulha Airport at 0700LT on a flight to Juiz de Fora, carrying six passengers and two pilots. In contact with Juiz de Fora Radio, the crew learned that the weather conditions at the aerodrome were below the IFR minima due to mist, and decided to maintain the route towards the destination and perform a non-precision RNAV (GNSS) IFR approach for landing on runway 03. During the final approach, the aircraft collided first with obstacles and then with the ground, at a distance of 245 meters from the runway 03 threshold, and exploded on impact. The aircraft was totally destroyed and all 8 occupants were killed, among them both President and Vice-President of the Vilmas Alimentos Group.

Probable cause:

The following factors were identified:

- The pilot may have displayed a complacent attitude, both in relation to the operation of the aircraft in general and to the need to accommodate his employers’ demands for arriving in SBJF. It is also possible to infer a posture of excessive self-confidence and confidence in the aircraft, in spite of the elements which signaled the risks inherent to the situation.

- It is possible that the different levels of experience of the two pilots, as well as the copilot’s personal features (besides being timid, he showed an excessive respect for the captain), may have resulted in a failure of communication between the crewmembers.

- It is possible that the captain’s leadership style and the copilot’s personal features resulted in lack of assertive attitudes on the part of the crew, hindering the exchange of adequate information, generating a faulty perception in relation to all the important elements of the environment, even with the aircraft alerts functioning in a perfect manner.

- The meteorological conditions in SBJF were below the minima for IFR operations on account of mist, with a ceiling at 100ft.

- The crew did not inform Juiz de Fora Radio about their passage of the MDA and, even without visual contact with the runway, deliberately continued in their descent, not complying with the prescriptions of the items 10.4 and 15.4 of the ICA 100-12 (Rules of the Air and Air Traffic Services).

- The crew judged that it would be possible to continue descending after the MDA, even without having the runway in sight.

- The pilot may have displayed a complacent attitude, both in relation to the operation of the aircraft in general and to the need to accommodate his employers’ demands for arriving in SBJF. It is also possible to infer a posture of excessive self-confidence and confidence in the aircraft, in spite of the elements which signaled the risks inherent to the situation.

- It is possible that the different levels of experience of the two pilots, as well as the copilot’s personal features (besides being timid, he showed an excessive respect for the captain), may have resulted in a failure of communication between the crewmembers.

- It is possible that the captain’s leadership style and the copilot’s personal features resulted in lack of assertive attitudes on the part of the crew, hindering the exchange of adequate information, generating a faulty perception in relation to all the important elements of the environment, even with the aircraft alerts functioning in a perfect manner.

- The meteorological conditions in SBJF were below the minima for IFR operations on account of mist, with a ceiling at 100ft.

- The crew did not inform Juiz de Fora Radio about their passage of the MDA and, even without visual contact with the runway, deliberately continued in their descent, not complying with the prescriptions of the items 10.4 and 15.4 of the ICA 100-12 (Rules of the Air and Air Traffic Services).

- The crew judged that it would be possible to continue descending after the MDA, even without having the runway in sight.

Final Report:

Crash of a Beechcraft B200 Super King Air in Atqasuk

Date & Time:

May 16, 2011 at 0218 LT

Registration:

N786SR

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Barrow - Atqasuk - Anchorage

MSN:

BB-1016

YOM:

1982

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

2

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

500.00

Aircraft flight hours:

9847

Circumstances:

The pilot had worked a 10-hour shift the day of the accident and had been off duty about 2 hours when the chief pilot called him around midnight to transport a patient. The pilot accepted the flight and, about 2 hours later, was on an instrument approach to the airport to pick up the patient. While on the instrument approach, all of the anti-ice and deice systems were turned on. The pilot said that the deice boots seemed to be shedding the ice almost completely. He extended the flaps and lowered the landing gear to descend; he then added power, but the airspeed continued to decrease. The airplane continued to descend, and he raised the flaps and landing gear and applied full climb power. The airplane shuddered as it climbed, and the airspeed continued to decrease. The stall warning horn came on, and the pilot lowered the nose to increase the airspeed. The airplane descended until it impacted level, snow-covered terrain. The airplane was equipped with satellite tracking and engine and flight control monitoring. The minimum safe operating speed for the airplane in continuous icing conditions is 140 knots indicated airspeed. The airplane's IAS dropped below 140 knots 4 minutes prior to impact. During the last 1 minute of flight, the indicated airspeed varied from a high of 124.5 knots to a low of 64.6 knots, and the vertical speed varied from 1,965 feet per minute to -2,464 feet per minute. The last data recorded prior to the impact showed that the airplane was at an indicated airspeed of 68 knots, descending at 1,651 feet per minute, and the nose was pitched up at 20 degrees. The pilot did not indicate that there were any mechanical issues with the airplane. The chief pilot reported that pilots are on call for 14 consecutive 24-hour periods before receiving two weeks off. He said that the accident pilot had worked the previous day but that the pilot stated that he was rested enough to accept the mission. The chief pilot indicated he was aware that sleep cycles and circadian rhythms are disturbed by varied and prolonged activity. An NTSB study found that pilots with more than 12 hours of time since waking made significantly more procedural and tactical decision errors than pilots with less than 12 hours of time since waking. A 2000 FAA study found accidents to be more prevalent among pilots who had been on duty for more than 10 hours, and a study by the U.S. Naval Safety Center found that pilots who were on duty for more than 10 of the last 24 hours were more likely to be involved in pilot-at-fault accidents than pilots who had less duty time. The operator’s management stated that they do not prioritize patient transportation with regard to their medical condition but base their decision to transport on a request from medical staff and availability of a pilot and aircraft, and suitable weather. The morning of the accident, the patient subsequently took a commercial flight to another hospital to receive medical treatment for his non-critical injury/illness. Given the long duty day and the early morning departure time of the flight, it is likely the pilot experienced significant levels of fatigue that substantially degraded his ability to monitor the airplane during a dark night instrument flight in icing conditions. The NTSB has issued numerous recommendations to improve emergency medical services aviation operations. One safety recommendation (A-06-13) addresses the importance of conducting a thorough risk assessment before accepting a flight. The safety recommendation asked the Federal Aviation Administration to "require all emergency medical services (EMS) operators to develop and implement flight risk evaluation programs that include training all employees involved in the operation, procedures that support the systematic evaluation of flight risks, and consultation with others trained in EMS flight operations if the risks reach a predefined level." Had such a thorough risk assessment been performed, the decision to launch a fatigued pilot into icing conditions late at night may have been different or additional precautions may have been taken to alleviate the risk. The NTSB is also concerned that the pressure to conduct EMS operations safely and quickly in various environmental conditions (for example, in inclement weather and at night) increases the risk of accidents when compared to other types of patient transport methods, including ground ambulances or commercial flights. However, guidelines vary greatly for determining the mode of and need for transportation. Thus, the NTSB recommended, in safety recommendation A-09-103, that the Federal Interagency Committee on Emergency Medical Services (FICEMS) "develop national guidelines for the selection of appropriate emergency transportation modes for urgent care." The most recent correspondence from FICEMS indicated that the guidelines are close to being finalized and distributed to members. Such guidance will help hospitals and physicians assess the appropriate mode of transport for patients.

Probable cause:

The pilot did not maintain sufficient airspeed during an instrument approach in icing conditions, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and loss of control. Contributing to the accident were the pilot’s fatigue, the operator’s decision to initiate the flight without conducting a formal risk assessment that included time of day, weather, and crew rest, and the lack of guidelines for the medical

community to determine the appropriate mode of transportation for patients.

community to determine the appropriate mode of transportation for patients.

Final Report:

Crash of a Beechcraft 200 Super King Air in Long Beach: 5 killed

Date & Time:

Mar 16, 2011 at 1029 LT

Registration:

N849BM

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Long Beach - Salt Lake City

MSN:

BB-849

YOM:

1981

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

5

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

5

Circumstances:

Witnesses reported that the airplane’s takeoff ground roll appeared to be normal. Shortly after the airplane lifted off, it stopped climbing and yawed to the left. Several witnesses heard abnormal sounds, which they attributed to propeller blade angle changes. The airplane’s flight path deteriorated to a left skid and its airspeed began to slow. The airplane’s left bank angle increased to between 45 and 90 degrees, and its nose dropped to a nearly vertical attitude. Just before impact, the airplane’s bank angle and pitch began to flatten out. The airplane had turned left about 100 degrees when it impacted the ground about 1,500 feet from the midpoint of the 10,000-foot runway. A fire then erupted, which consumed the fuselage. Review of a security camera video of the takeoff revealed that the airplane was near the midpoint of the runway, about 140 feet above the ground, and at a ground speed of about 130 knots when it began to yaw left. The left yaw coincided with the appearance, behind the airplane, of a dark grayish area that appeared to be smoke. A witness, who was an aviation mechanic with extensive experience working on airplanes of the same make and model as the accident airplane, reported hearing two loud “pops” about the time the smoke appeared, which he believed were generated by one of the engines intermittently relighting and extinguishing. Post accident examination of the airframe, the engines, and the propellers did not identify any anomalies that would have precluded normal operation. Both engines and propellers sustained nearly symmetrical damage, indicating that the two engines were operating at similar low- to mid-range power settings at impact. The airplane’s fuel system was comprised of two separate fuel systems (one for each engine) that consisted of multiple wing fuel tanks feeding into a nacelle tank and then to the engine. The left and right nacelle tanks were breached during the impact sequence and no fuel was found in either tank. Samples taken from the fuel truck, which supplied the airplane's fuel, tested negative for contamination. However, a fuels research engineer with the United States Air Force Fuels Engineering Research Laboratory stated that water contamination can result from condensation in the air cavity above a partially full fuel tank. Both diurnal temperature variations and the atmospheric pressure variations experienced with normal flight cycles can contribute to this type of condensation. He stated that the simplest preventive action is to drain the airplane’s fuel tank sumps before every flight. There were six fuel drains on each wing that the Pilot’s Operating Handbook (POH) for the airplane dictated should be drained before every flight. The investigation revealed that the pilot’s previous employer, where he had acquired most of his King Air 200 flight experience, did not have its pilots drain the fuel tank sumps before every flight. Instead, maintenance personnel drained the sumps at some unknown interval. No witnesses were identified who observed the pilot conduct the preflight inspection of the airplane before the accident flight, and it could not be determined whether the pilot had drained the airplane’s fuel tank sumps. He had been the only pilot of the airplane for its previous 40 flights. Because the airplane was not on a Part 135 certificate or a continuous maintenance program, it is unlikely that a mechanic was routinely draining the airplane's fuel sumps. The witness observations, video evidence, and the postaccident examination indicated that the left engine experienced a momentary power interruption during the takeoff initial climb, which was consistent with a power interruption resulting from water contamination of the left engine's fuel supply. It is likely that, during the takeoff rotation and initial climb, water present in the bottom of the left nacelle tank was drawn into the left engine. When the water flowed through the engine's fuel nozzles into the burner can, it momentarily extinguished the engine’s fire. The engine then stopped producing power, and its propeller changed pitch, resulting in the propeller noises heard by witnesses. Subsequently, a mixture of water and fuel reached the nozzles and the engine intermittently relighted and extinguished, which produced the grayish smoke observed in the video and the “pop” noises heard by the mechanic witness. Finally, uncontaminated fuel flow was reestablished, and the engine resumed normal operation. About 5 months before the accident, the pilot successfully completed a 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 135 pilot-in-command check flight in a King Air 90. However, no documentation was found indicating that he had ever received training in a full-motion King Air simulator. Although simulator training was not required, if the pilot had received this type of training, it is likely that he would have been better prepared to maintain directional control in response to the left yaw from asymmetrical power. Given that the airplane’s airspeed was more than 40 knots above the minimum control speed of 86 knots when the left yaw began, the pilot should have been able to maintain directional control during the momentary power interruption. Although the airplane’s estimated weight at the time of the accident was about 650 pounds over the maximum allowable gross takeoff weight of 12,500 pounds, the investigation determined that the additional weight would not have precluded the pilot from maintaining directional control of the airplane.

Probable cause:

The pilot’s failure to maintain directional control of the airplane during a momentary interruption of power from the left engine during the initial takeoff climb. Contributing to the accident was the power interruption due to water contamination of the fuel, which was likely not drained from the fuel tanks by the pilot during preflight inspection as required in the POH.

Final Report: