Crash of a Boeing 747-244BSF in Halifax: 7 killed

Date & Time:

Oct 14, 2004 at 0356 LT

Registration:

9G-MKJ

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Windsor Locks - Halifax - Zaragoza

MSN:

22170

YOM:

1980

Flight number:

MKA1602

Crew on board:

7

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

7

Aircraft flight hours:

80619

Aircraft flight cycles:

16368

Circumstances:

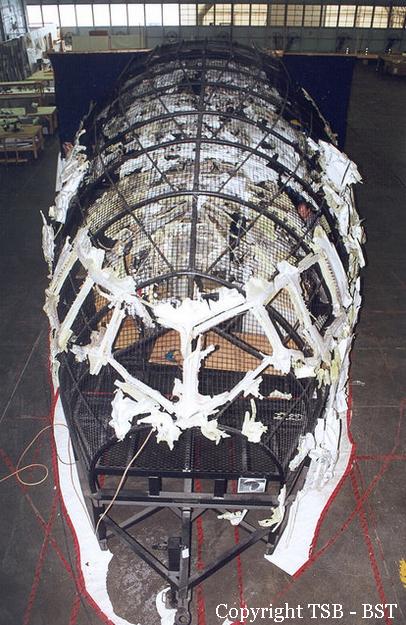

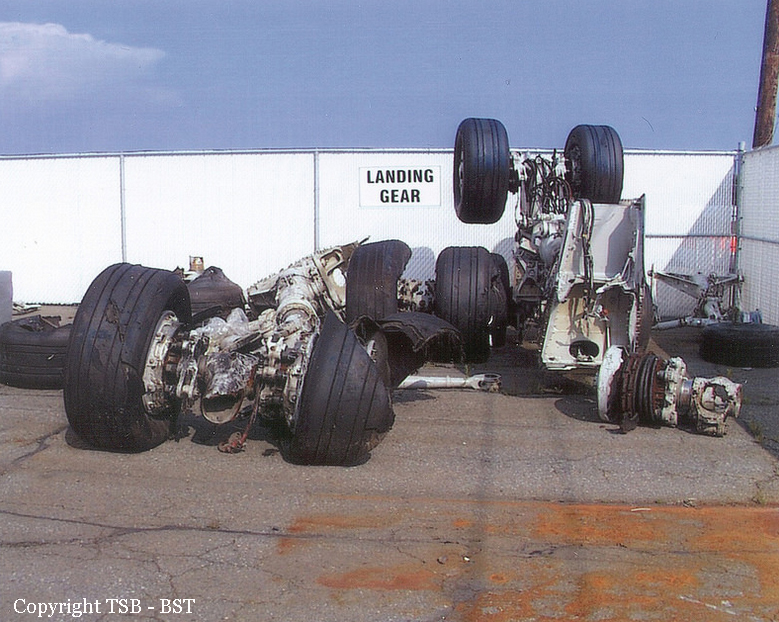

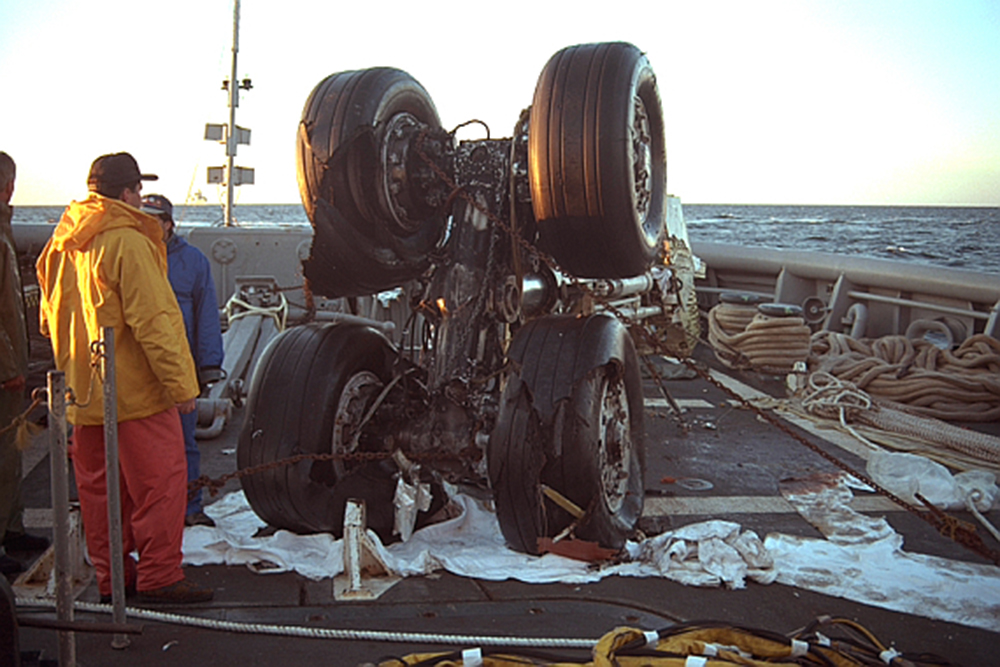

MKA1602 landed on Runway 24 at Halifax International Airport at 0512 and taxied to the ramp. After shutdown, loading of the aircraft was started. During the loading, two MK Airlines Limited crew members were observed sleeping in the upper deck passenger seats. After the fuelling was complete, the ground engineer checked the aircraft fuelling panel and signed the fuel ticket. The aircraft had been uploaded with 72 062 kg of fuel, for a total fuel load of 89 400 kg. The ground engineer then went to the main cargo deck to assist with the loading. Once the loading was complete, the ramp supervisor for the ground handling agent went to the upper deck to retrieve the MKA1602 cargo and flight documentation. While the loadmaster was completing the documentation, the ramp supervisor visited the cockpit and noted that the first officer was not in his seat. Approximately 10 minutes later, the ramp supervisor, with the documentation, left the aircraft. At 0647, the crew began taxiing the aircraft to position on Runway 24, and at 0653, the aircraft began its take-off roll. See Section 1.11.4 of this report for a detailed sequence of events for the take-off. During rotation, the aircraftís lower aft fuselage briefly contacted the runway. A few seconds later, the aircraftís lower aft fuselage contacted the runway again but with more force. The aircraft remained in contact with the runway and the ground to a point 825 feet beyond the end of the runway, where it became airborne and flew a distance of 325 feet. The lower aft fuselage then struck an earthen berm supporting an instrument landing system (ILS) localizer antenna. The aircraft's tail separated on impact, and the rest of the aircraft continued in the air for another 1200 feet before it struck terrain and burst into flames. The final impact was at latitude 44°52'51" N and longitude 063°30'31" W, approximately 2500 feet past the departure end of Runway 24, at an elevation of 403 feet above sea level (asl). The aircraft was destroyed by impact forces and post-crash fire. All persons on board (seven crew members) were fatally injured.

Probable cause:

Findings as to Causes and Contributing Factors:

1. The Bradley take-off weight was likely used to generate the Halifax take-off performance data, which resulted in incorrect V speeds and thrust setting being transcribed to the take-off data card.

2. The incorrect V speeds and thrust setting were too low to enable the aircraft to take off safely for the actual weight of the aircraft.

3. It is likely that the flight crew member who used the Boeing Laptop Tool (BLT) to generate take-off performance data did not recognize that the data were incorrect for the planned take-off weight in Halifax. It is most likely that the crew did not adhere to the operatorís procedures for an independent check of the take-off data card.

4. The pilots of MKA1602 did not carry out the gross error check in accordance with the company's standard operating procedures (SOPs), and the incorrect take-off performance data were not detected.

5. Crew fatigue likely increased the probability of error during calculation of the take-off performance data, and degraded the flight crewís ability to detect this error.

6. Crew fatigue, combined with the dark take-off environment, likely contributed to a loss of situational awareness during the take-off roll. Consequently, the crew did not recognize the inadequate take-off performance until the aircraft was beyond the point where the take-off could be safely conducted or safely abandoned.

7. The aircraftís lower aft fuselage struck a berm supporting a localizer antenna, resulting in the tail separating from the aircraft, rendering the aircraft uncontrollable.

8. The company did not have a formal training and testing program on the BLT, and it is likely that the user of the BLT in this occurrence was not fully conversant with the software.

Findings as to Risk:

1. Information concerning dangerous goods and the number of persons on board was not readily available, which could have jeopardized the safety of the rescue personnel and aircraft occupants.

2. Failure of one of the airport emergency power generators to provide backup power prevented the operation of some automatic functions at the fire hall after the crash alarm was activated, increasing the potential for a delayed response.

3. Grid map coordinates were not used to direct units responding to the crash and some responding units did not have copies of the grid map. The non-use of grid coordinates during an emergency could lead to confusion and increase response times.

4. Communication difficulties encountered by the emergency response agencies complicated coordination and could have hampered a rescue attempt or quick evacuation of an injured person.

5. A faulty aircraft cargo loading system prevented the proper positioning of a roll of steel, resulting in the weight limits of positions LR and MR being exceeded by 4678 kg (50 per cent).

6. The company increase of the maximum flight duty time for a heavy crew from 20 to 24 hours increased the potential for fatigue.

7. Regulatory oversight of MK Airlines Limited by the Ghana Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) was not adequate to detect serious non-conformances to flight and duty times, nor ongoing non-adherence to company directions and procedures.

8. The delay in passing the new Civil Aviation Act, 2004 hindered the GCAAís ability to exercise effective oversight of MK Airlines Limited.

9. Company planning and execution of very long flight crew duty periods substantially increased the potential for fatigue.

10. The company expansion, flight crew turnover, and the MK Airlines Limited recruitment policy resulted in a shortage of flight crew; consequently, fewer crews were available to meet operational demands, increasing stress and the potential for fatigue.

11. There were no regulations or company rules governing maximum duty periods for loadmasters and ground engineers, resulting in increased potential for fatigue-induced errors.

12. The MK Airlines Limited flight operations quality and flight safety program was in the early stages of development at the time of the accident; consequently, it had limited effectiveness.

13. The berms located at either end of runways 06 and 24 were not evaluated as to whether they were a hazard to aircraft in the runway overrun/undershoot areas.

14. The operating empty weight of the aircraft did not include 1120 kg of personnel and equipment; consequently, it was possible that the maximum allowable aircraft weights could be exceeded unknowingly.

15. The ground handling agent at Halifax International Airport did not have the facilities to weigh built-up pallets that were provided by others. Incorrect load weights could result in adverse aircraft performance.

16. Some MK Airlines Limited flight crew members did not adhere to all company SOPs; company and regulatory oversight did not address this deficiency.

Other Findings:

1. An incorrect slope for Runway 24 was published in error and not detected; the effect of this discrepancy was not a significant factor in the operation of MKA1602 at Halifax.

2. The occurrence aircraft was within the weight and centre of gravity limits for the occurrence flight, although the allowable cargo weights on positions LR and MR were exceeded.

3. Based on engineering simulation, the accident aircraft performance was consistent with that expected for the configuration, weight and conditions for the attempted take-off at Halifax International Airport.

4. There have been several examples of incidents and accidents worldwide where non-adherence to procedures has led to incorrect take-off data being used, and the associated flight crews have not recognized the inadequate take-off performance. 5. No technical fault was found with the aircraft or engines that would have contributed to the accident.

1. The Bradley take-off weight was likely used to generate the Halifax take-off performance data, which resulted in incorrect V speeds and thrust setting being transcribed to the take-off data card.

2. The incorrect V speeds and thrust setting were too low to enable the aircraft to take off safely for the actual weight of the aircraft.

3. It is likely that the flight crew member who used the Boeing Laptop Tool (BLT) to generate take-off performance data did not recognize that the data were incorrect for the planned take-off weight in Halifax. It is most likely that the crew did not adhere to the operatorís procedures for an independent check of the take-off data card.

4. The pilots of MKA1602 did not carry out the gross error check in accordance with the company's standard operating procedures (SOPs), and the incorrect take-off performance data were not detected.

5. Crew fatigue likely increased the probability of error during calculation of the take-off performance data, and degraded the flight crewís ability to detect this error.

6. Crew fatigue, combined with the dark take-off environment, likely contributed to a loss of situational awareness during the take-off roll. Consequently, the crew did not recognize the inadequate take-off performance until the aircraft was beyond the point where the take-off could be safely conducted or safely abandoned.

7. The aircraftís lower aft fuselage struck a berm supporting a localizer antenna, resulting in the tail separating from the aircraft, rendering the aircraft uncontrollable.

8. The company did not have a formal training and testing program on the BLT, and it is likely that the user of the BLT in this occurrence was not fully conversant with the software.

Findings as to Risk:

1. Information concerning dangerous goods and the number of persons on board was not readily available, which could have jeopardized the safety of the rescue personnel and aircraft occupants.

2. Failure of one of the airport emergency power generators to provide backup power prevented the operation of some automatic functions at the fire hall after the crash alarm was activated, increasing the potential for a delayed response.

3. Grid map coordinates were not used to direct units responding to the crash and some responding units did not have copies of the grid map. The non-use of grid coordinates during an emergency could lead to confusion and increase response times.

4. Communication difficulties encountered by the emergency response agencies complicated coordination and could have hampered a rescue attempt or quick evacuation of an injured person.

5. A faulty aircraft cargo loading system prevented the proper positioning of a roll of steel, resulting in the weight limits of positions LR and MR being exceeded by 4678 kg (50 per cent).

6. The company increase of the maximum flight duty time for a heavy crew from 20 to 24 hours increased the potential for fatigue.

7. Regulatory oversight of MK Airlines Limited by the Ghana Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) was not adequate to detect serious non-conformances to flight and duty times, nor ongoing non-adherence to company directions and procedures.

8. The delay in passing the new Civil Aviation Act, 2004 hindered the GCAAís ability to exercise effective oversight of MK Airlines Limited.

9. Company planning and execution of very long flight crew duty periods substantially increased the potential for fatigue.

10. The company expansion, flight crew turnover, and the MK Airlines Limited recruitment policy resulted in a shortage of flight crew; consequently, fewer crews were available to meet operational demands, increasing stress and the potential for fatigue.

11. There were no regulations or company rules governing maximum duty periods for loadmasters and ground engineers, resulting in increased potential for fatigue-induced errors.

12. The MK Airlines Limited flight operations quality and flight safety program was in the early stages of development at the time of the accident; consequently, it had limited effectiveness.

13. The berms located at either end of runways 06 and 24 were not evaluated as to whether they were a hazard to aircraft in the runway overrun/undershoot areas.

14. The operating empty weight of the aircraft did not include 1120 kg of personnel and equipment; consequently, it was possible that the maximum allowable aircraft weights could be exceeded unknowingly.

15. The ground handling agent at Halifax International Airport did not have the facilities to weigh built-up pallets that were provided by others. Incorrect load weights could result in adverse aircraft performance.

16. Some MK Airlines Limited flight crew members did not adhere to all company SOPs; company and regulatory oversight did not address this deficiency.

Other Findings:

1. An incorrect slope for Runway 24 was published in error and not detected; the effect of this discrepancy was not a significant factor in the operation of MKA1602 at Halifax.

2. The occurrence aircraft was within the weight and centre of gravity limits for the occurrence flight, although the allowable cargo weights on positions LR and MR were exceeded.

3. Based on engineering simulation, the accident aircraft performance was consistent with that expected for the configuration, weight and conditions for the attempted take-off at Halifax International Airport.

4. There have been several examples of incidents and accidents worldwide where non-adherence to procedures has led to incorrect take-off data being used, and the associated flight crews have not recognized the inadequate take-off performance. 5. No technical fault was found with the aircraft or engines that would have contributed to the accident.

Final Report: