Country

Operator Image

Crash of a McDonnell Douglas MD-83 off Anacapa Island: 88 killed

Date & Time:

Jan 31, 2000 at 1620 LT

Registration:

N963AS

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Puerto Vallarta - San Francisco - Seattle - Anchorage

MSN:

53077

YOM:

1992

Flight number:

AS261

Crew on board:

5

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

83

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

88

Captain / Total hours on type:

4150.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

8060

Aircraft flight hours:

26584

Aircraft flight cycles:

14315

Circumstances:

On January 31, 2000, about 1621 Pacific standard time, Alaska Airlines, Inc., flight 261, a McDonnell Douglas MD-83, N963AS, crashed into the Pacific Ocean about 2.7 miles north of Anacapa Island, California. The 2 pilots, 3 cabin crewmembers, and 83 passengers on board were killed, and the airplane was destroyed by impact forces. Flight 261 was operating as a scheduled international passenger flight under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121 from Lic Gustavo Diaz Ordaz International Airport, Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, Seattle, Washington, with an intermediate stop planned at San Francisco International Airport, San Francisco, California. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed for the flight, which operated on an instrument flight rules flight plan.

Probable cause:

A loss of airplane pitch control resulting from the in-flight failure of the horizontal stabilizer trim system jackscrew assembly's acme nut threads. The thread failure was caused by excessive wear resulting from Alaska Airlines' insufficient lubrication of the jackscrew assembly. Contributing to the accident were Alaska Airlines' extended lubrication interval and the Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA) approval of that extension, which increased the likelihood that a missed or inadequate lubrication would result in excessive wear of the acme nut threads, and Alaska Airlines' extended end play check interval and the FAA's approval of that extension, which allowed the excessive wear of the acme nut threads to progress to failure without the opportunity for detection. Also contributing to the accident was the absence on the McDonnell Douglas MD-80 of a fail-safe mechanism to prevent the catastrophic effects of total acme nut thread loss.

Final Report:

Ground accident of a Boeing 727-90C in Anchorage

Date & Time:

Jun 9, 1987 at 0855 LT

Registration:

N766AS

Survivors:

Yes

MSN:

19728

YOM:

1968

Crew on board:

2

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Aircraft flight hours:

49937

Circumstances:

The mechanic in charge of taxiing the Boeing 727 allowed an unauthorized avionics technician to occupy the pilot seat. They inadvertently deactivated the brake pressurization system and struck a passenger jetway at the terminal gate. An ensuing fire destroyed the airplane and a company ground vehicle and extensively damaged the jetway. The terminal gate was also damaged. A total of 11 persons were injured.

Probable cause:

Occurrence #1: on ground/water collision with object

Phase of operation: taxi

Findings

1. Object - airport facility

2. (c) brakes (normal) - inadvertent deactivation - company maintenance personnel

3. (f) planning/decision - inadequate - company maintenance personnel

4. (c) checklist - not used - company maintenance personnel

----------

Occurrence #2: fire

Phase of operation: other

Phase of operation: taxi

Findings

1. Object - airport facility

2. (c) brakes (normal) - inadvertent deactivation - company maintenance personnel

3. (f) planning/decision - inadequate - company maintenance personnel

4. (c) checklist - not used - company maintenance personnel

----------

Occurrence #2: fire

Phase of operation: other

Final Report:

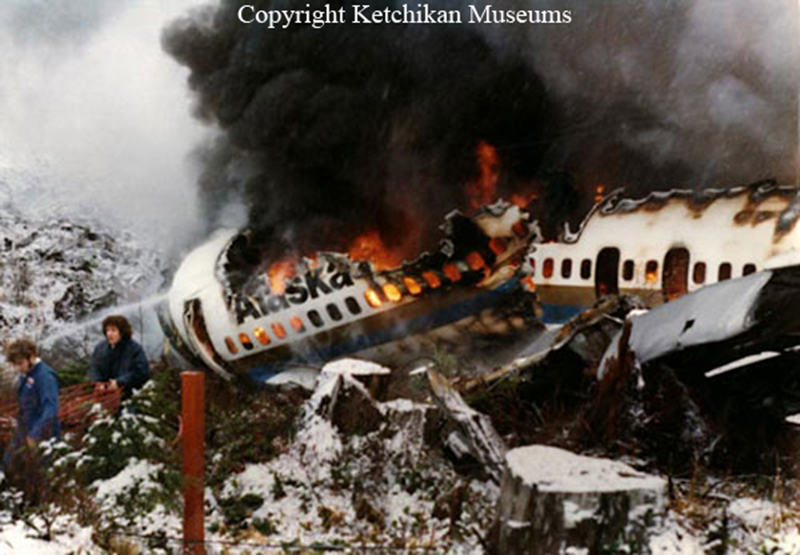

Crash of a Boeing 727-81 in Ketchikan: 1 killed

Date & Time:

Apr 5, 1976 at 0819 LT

Registration:

N124AS

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Anchorage - Juneau - Ketchikan - Seattle

MSN:

18821/124

YOM:

1965

Flight number:

AS060

Crew on board:

7

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

43

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

1

Captain / Total hours on type:

2140.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

1980

Aircraft flight hours:

25360

Circumstances:

About 0738LT on April 5, 1976, Alaska Airlines, Inc., Flight 60, a B-727-81, N124AS, departed Juneau, Alaska, on a regularly scheduled passenger flight to Seattle, Washington; an en route stop was scheduled for Ketchikan International Airport, Ketchikan, Alaska. There were 43 passengers and a crew of 7 on board. Anchorage air route traffic control center (ARTCC) cleared Flight 60 on an instrument flight rules (IFR) flight plan to the Ketchikan International Airport; the flight was routine en route. At 0805, Anchorage ARTCC cleared Flight 60 for an approach to runway 11 at Ketchikan. At 0807, the flight was 30 DME miles from the airport. At 0811, Flight 60 reported out of 10,000 feet and was cleared to contact Ketchikan Flight Service Station (FSS); the FSS advised the flight that the 0805 weather was: ceiling 800 ft., obscured, visibility 2 mi, light snow, fog, wind 330° at 5 kt. The FSS also advised the flight that braking action on runway 11 was poor; this report was based on braking tests performed by the airport manager. The captain testified that he did not recall hearing the braking condition report. Upon receipt of the clearance, the crew of Flight 60 began an ILS approach to Ketchikan. Near the 17-mile DME fix, as the flight descended through 4,000 feet, the crew acquired visual contact with the ground and water. As the flight approached Guard Island, the captain had the Island in sight and decided to abandon the ILS approach and to continue the approach visually. The captain testified that he established a 'visual glide slope of my own' at an altitude of about 1,000 feet, and stated that his eyes were '... the most reliable thing I have.' Visual contact with the approach lights was established about 2 miles from the runway threshold. The airport was visible shortly thereafter. The captain did not recall the airspeed at touchdown, but estimated that he touched down about 1,500 feet past the threshold of runway 11. He also testified that he did not see the yellow, 1,000-foot markers on the runway; he further testified that the runway '... was just wet.' A passenger on Flight 60, who was seated in seat 5A (just forward of the wing's leading edge), stated that the yellow runway marks were visible to him. The first officer has no recollection of the sequence of events leading to the accident; however, the second officer testified that airspeeds and descent rates were called out during the last 1,000 feet. The captain could not recall the flap setting either on approach or at touchdown. However, the second officer testified that after the landing gear was extended the first officer remarked, 'We're high,' and lowered the flaps from 30° to 40°. None of the cockpit crew remembered the airspeeds, descent rates, or altitudes of the aircraft during the approach and touchdown. Reference speed was calculated to be 117 kns with 40° flaps and 121 kns with 30° flaps. The captain testified that after touchdown he deployed the ground spoilers, reversed the engines, and applied the wheel brakes. Upon discovering that the braking action was poor, he decided to execute a go-around. He retracted the ground spoilers, called for 25° flaps, and attempted to obtain takeoff thrust. The thrust reverser mechanism did not disengage fully and the forward thrust could not be obtained. He then applied full reversing and quickly moved the thrust levers to 'idle.' This attempt to obtain forward thrust also was not successful. The captain then reapplied reverse thrust and again deployed the ground spoilers in an attempt to slow the aircraft. When he realized that the aircraft could not be stopped on the runway, he turned the aircraft to the right, raised the nose, and passed over a gully and a service road beyond the departure end of the runway. The aircraft came to rest in a ravine, 700 feet past the departure end of runway 11 and 125 feet to the right of the runway centerline. Flight attendants reported nothing unusual about the approach and touchdown, except for the relatively short time between the illumination of the no-smoking sign and the touchdown. The two flight attendants assigned to the rear jumpseats and the attendant assigned to the forward jumpseat did not have sufficient time to reach their assigned seats and had to sit in passenger seats. None of the flight attendants felt the aircraft decelerate or heard normal reverse thrust. Many passengers anticipated the accident because of the high speed of the aircraft after touchdown and the lack of deceleration. Two ground witnesses, who are also pilots, saw the aircraft when it was at an altitude of 500 to 700 feet and in level flight. The witnesses were located about 7,000 feet northwest of the threshold of runway 11. They stated that the landing gear was up and that the aircraft seemed to be 'fast' for that portion of the approach. When the aircraft disappeared behind an obstruction, these witnesses moved to another location to continue watching the aircraft. They saw the nose gear in transit and stated that it appeared to be completely down as the aircraft crossed over the first two approach lights. The first two approach lights are located about 3,000 feet from the runway threshold. A witness, who was located on the fifth floor of the airport terminal, saw the aircraft when it was about 25 feet over the runway. The witness stated that the aircraft was in a level attitude, but that it appeared 'very fast.' He stated that the aircraft touched down about one-quarter way down the runway, that it bounced slightly, and that it landed again on the nose gear only. It then began a porpoising motion which continued until the aircraft was past midfield. Most witnesses placed the touchdown between one-quarter and one-half way down the runway and reported that the aircraft seemed faster-than-normal during the landing roll. Witnesses reported varying degrees of reverse thrust, but most reported only a short burst of reverse thrust as the aircraft passed the airport terminal, about 3,800 feet past the threshold of runway 11.

Probable cause:

The captain's faulty judgement in initiating a go-around after he was committed to a full stop landing following an excessively long and fast touchdown from an unstabilized approach. Contributing to the accident was the pilot's unprofessional decision to abandon the precision approach. The following findings were reported:

- There is no evidence of aircraft structure or component failure or malfunction before the aircraft crashed.

- The flight crew was aware of the airport and weather conditions at Ketchikan.

- The weather conditions and runway conditions dictated that a precision approach should have been flown.

- The approach was not made according to prescribed procedures and was not stabilized. The aircraft was not in the proper position at decision height to assure a safe landing because of excessive airspeed, excessive altitude, and improperly configured flaps and landing gear.

- The aircraft's altitude was higher-than-normal when it crossed the threshold of runway 11 and its airspeed was excessively high.

- The captain did not use good judgment when he initiated a go-around after he was committed to full-stop landing following the touchdown.

- There is no evidence that the first and second officers apprised the captain of his departure from prescribed procedures and safe practices, or that they acted in any way to assure a more professional performance, except for the comment by the first officer, when near the threshold, that they were high after which he lowered the flaps to 40°.

- After applying reverse thrust shortly after touchdown, the captain was unable to regain forward thrust because the high speed of the aircraft produced higher-than-normal airloads on the thrust deflector doors.

- Braking action on runway 11 was adequate for stopping the aircraft before it reached the departure end of the runway.

- Before the accident the FAA had not determined adequately the airport's firefighting capabilities.

- Postaccident hearing tests conducted on the captain indicated a medically disqualifying hearing loss; however, the evidence was inadequate to conclude that this condition had any bearing on the accident.

- There is no evidence of aircraft structure or component failure or malfunction before the aircraft crashed.

- The flight crew was aware of the airport and weather conditions at Ketchikan.

- The weather conditions and runway conditions dictated that a precision approach should have been flown.

- The approach was not made according to prescribed procedures and was not stabilized. The aircraft was not in the proper position at decision height to assure a safe landing because of excessive airspeed, excessive altitude, and improperly configured flaps and landing gear.

- The aircraft's altitude was higher-than-normal when it crossed the threshold of runway 11 and its airspeed was excessively high.

- The captain did not use good judgment when he initiated a go-around after he was committed to full-stop landing following the touchdown.

- There is no evidence that the first and second officers apprised the captain of his departure from prescribed procedures and safe practices, or that they acted in any way to assure a more professional performance, except for the comment by the first officer, when near the threshold, that they were high after which he lowered the flaps to 40°.

- After applying reverse thrust shortly after touchdown, the captain was unable to regain forward thrust because the high speed of the aircraft produced higher-than-normal airloads on the thrust deflector doors.

- Braking action on runway 11 was adequate for stopping the aircraft before it reached the departure end of the runway.

- Before the accident the FAA had not determined adequately the airport's firefighting capabilities.

- Postaccident hearing tests conducted on the captain indicated a medically disqualifying hearing loss; however, the evidence was inadequate to conclude that this condition had any bearing on the accident.

Final Report:

Crash of a Boeing 727-193 near Juneau: 111 killed

Date & Time:

Sep 4, 1971 at 1215 LT

Registration:

N2969G

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Anchorage – Cordova – Yakutat – Juneau – Sitka – Seattle

MSN:

19304/287

YOM:

1966

Flight number:

AS1866

Crew on board:

7

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

104

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

111

Captain / Total hours on type:

2688.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

2100

Aircraft flight hours:

11344

Circumstances:

Alaska Airlines, Flight 1866 (AS66) was a scheduled passenger flight from Anchorage (ANC), to Seattle (SEA), with intermediate stops at Cordova (CDV), Yakutat (YAK), Juneau (JNU), and Sitka (SIT). The IFR flight departed Anchorage at 09:13 and landed at Cordova at 09:42. AS66 departed Cordova at 10:34 after a delay, part of which was attributable to difficulty in securing a cargo compartment door. The flight landed at Yakutat at 11:07. While on the ground, AS66 received an air traffic control clearance to the Juneau Airport via Jet Route 507 to the Pleasant Intersection, direct to Juneau, to maintain 9,000 feet or below until 15 miles southeast of Yakutat on course, then to climb to and maintain FL230. The flight departed Yakutat at 11:35, with 104 passengers and seven crew members on board. At 11:46, AS66 contacted the Anchorage ARTCC and reported level at FL230, 65 miles east of Yakutat. The flight was then cleared to descend at the pilot's discretion to maintain 10,000 ft so as to cross the Pleasant Intersection at 10,000 feet and was issued a clearance limit to the Howard Intersection. The clearance was acknowledged correctly by the captain and the controller provided the Juneau altimeter setting of 29.46 inches and requested AS66 to report leaving 11,000 ft. At 11:51, AS66 reported leaving FL230. Following this report, the flight's clearance limit was changed to the Pleasant Intersection. At 11:54, the controller instructed AS66 to maintain 12,000 feet. Approximately 1 minute later, the flight reported level at 12,000 feet. The changes to the flight's original clearance to the Howard Intersection were explained to AS66 by the controller as follows: "I've got an airplane that's not following his clearance, I've got to find out where he is." The controller was referring to N799Y, a Piper Apache which had departed Juneau at 11:44 on an IFR clearance, destination Whitehorse, Canada. On two separate occasions, AS66 acted as communications relay between the controller and N799Y. At 11:58, AS66 reported that they were at the Pleasant Intersection, entering the holding pattern, whereupon the controller recleared the flight to Howard Intersection via the Juneau localizer. In response to the controller's query as to whether the flight was "on top" at 12,000 feet, the captain stated that the flight was "on instruments." At 12:00, the controller repeated the flight's clearance to hold at Howard Intersection and issued an expected approach time of 12:10. At 12:01, AS66 reported that they were at Howard, holding 12,000 feet. Six minutes later, AS66 was queried with respect to the flight's direction of holding and its position in the holding pattern. When the controller was advised that the flight had just completed its inbound turn and was on the localizer, inbound to Howard, he cleared AS66 for a straight-in LDA approach, to cross Howard at or below 9,000 feet inbound. The captain acknowledged the clearance and reported leaving 12,000 feet. At 12:08 the captain reported "leaving five thousand five ... four thousand five hundred," whereupon the controller instructed AS66 to contact Juneau Tower. Contact with the tower was established shortly thereafter when the captain reported, "Alaska sixty-six Barlow inbound." (Barlow Intersection is located about 10 nautical miles west of the Juneau Airport). The Juneau Tower Controller responded, "Alaska 66, understand, ah, I didn't, ah, copy the intersection, landing runway 08, the wind 080° at 22 occasional gusts to 28, the altimeter now 29.47, time is 09 1/2, call us by Barlow". No further communication was heard from the flight. The Boeing 727 impacted the easterly slope of a canyon in the Chilkat Range of the Tongass National Forest at the 2475-foot level. The aircraft disintegrated on impact. The accident was no survivable.

Probable cause:

A display of misleading navigational information concerning the flight's progress along the localizer course which resulted in a premature descent below obstacle clearance altitude. The origin or nature of the misleading navigational information could not be determined. The Board further concludes that the crew did not use all available navigational aids to check the flight's progress along the localizer nor were these aids required to be used. The crew also did not perform the required audio identification of the pertinent navigational facilities.

Final Report:

Crash of a Lockheed L-1049H Super Constellation in Kotzebue

Date & Time:

Apr 17, 1967 at 1452 LT

Registration:

N7777C

Survivors:

Yes

MSN:

4803

YOM:

1956

Crew on board:

4

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

28

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

2017.00

Circumstances:

The approach to Kotzebue-Wien Memorial Airport was completed in whiteout conditions with a very limited visibility. Following a 'normal' approach, the airplane belly landed and slid for few hundred yards before coming to rest. All 32 occupants were evacuated while the aircraft was damaged beyond repair.

Probable cause:

The crew failed to follow the approach check-list and forgot to lower the landing gear, causing the airplane to make a wheels-up landing.

Final Report:

Crash of a Douglas DC-6A in Shemya: 6 killed

Date & Time:

Jul 21, 1961 at 0211 LT

Registration:

N6118C

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Everett – Travis – Anchorage – Shemya – Tachikawa

MSN:

45243

YOM:

1958

Flight number:

CKA779

Crew on board:

6

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

6

Captain / Total hours on type:

1118.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

101

Aircraft flight hours:

10600

Circumstances:

Flight CKA779 was a Military Air Transport Service (MATS) contract flight. It originated at Everett-Paine AFB, WA (PAE), on July 20, 1961, and proceeded to Fairfield-Travis AFB, CA (SUU). At Travis AFB 25,999 pounds of cargo was loaded. The flight then departed Travis and flew non-stop to Anchorage, Alaska. At Anchorage, the crew received weather and NOTAM information for the flight to Shemya AFB, AK (SYA), which did not include the approach or field lighting deficiencies. The stop at Shemya was for the purpose of servicing the aircraft before proceeding to Tachikawa AB, Japan for refueling. The flight took off from Anchorage at 19:40 and proceeded routinely toward Shemya. The flight made contact with Shemya Radio at 00:45. It was flying at FL100 between layers of clouds. At 01:28 the crew reported 100 miles east of Shemya, estimating Shemya at 01:55. Shemya Radio cleared the flight inbound to Shemya Homer and to descend and maintain 5,500 feet. At 01:45, the flight contacted Shemya GCA and radar contact was made approximately 18 miles north-northeast of Shemya, at 5,500 feet. The GCA controller transmitted the following weather information: "Indefinite ceiling 200 feet; sky obscured, visibility one mile in fog; new altimeter 29.86." According to the GCA controller, the DC-6 intercepted the glide path for runway 10 properly and maintained a good course. When two miles from touchdown, it dropped approximately 10 to 25 feet below the glide path. At one mile out, the flight went an estimated 30 to 40 feet below the glide path, which was still well above the minimum safe altitude for the approach. When the flight, was over the approach lights, it started to descend rapidly. The aircraft struck an embankment, approx. 200 feet short of the threshold in a nearly level attitude, the nose wheel touching first, about 18 feet below the crest, very nearly aligned with the centerline of the runway. The aircraft slid up the embankment during impact and when it reached the crest, broke in two at the leading edge of the wings. The fuselage, wings, and tail section stopped and settled back on the slope. The powerplants, nose section, and the bulk of the cargo slid varying distances toward the runway and up on it for a distance of about 100 yards. Fire followed impact and the majority of the wreckage was consumed.

Probable cause:

The absence of approach and runway lights, and the failure of the GCA controller to give more positive guidance to the pilot during the last stages of his approach.

Final Report:

Crash of a Douglas C-118A Liftmaster at Elmendorf AFB

Date & Time:

Feb 22, 1960

Registration:

N11817

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Anchorage - Elmendorf

MSN:

44653

YOM:

1955

Crew on board:

4

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

0

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Circumstances:

The crew was performing a positioning flight from Anchorage International Airport to Elmendorf AFB. The approach was completed in marginal weather conditions with a limited visibility due to fog. On final, the four engine aircraft was too low and struck the ground 1,200 feet short of runway threshold. All four crew members were rescued while the aircraft was written off.

Probable cause:

Wrong approach configuration on part of the captain had used an rpm setting of 2200 instead of 2400 during the approach, power setting of 20" manifold pressure instead of 25" and a 40° flap setting instead of 30°. The first officer and the flight engineer were aware of this but failed to report it to the captain. Furthermore, the GCA controller advised the flight that it was below the limits of the glide path.

Crash of a Douglas C-54B-20-DO Skymaster near Blyn: 5 killed

Date & Time:

Mar 2, 1957 at 1719 LT

Registration:

N90449

Survivors:

No

Schedule:

Fairbanks – Seattle

MSN:

27239

YOM:

1944

Flight number:

AS100

Crew on board:

3

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

2

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

5

Captain / Total hours on type:

8023.00

Copilot / Total hours on type:

4532

Aircraft flight hours:

28835

Circumstances:

Alaska Airlines, Inc., is an air carrier certificated to conduct scheduled operations within the Territory of Alaska and between Alaska and the continental United States. Flight 100 of March 2 originated at Fairbanks, Alaska, as a regularly scheduled nonstop flight to Seattle, Washington. The aircraft, N 90449, had arrived from Seattle at 0717 March 2 as Trip 101/1. Two minor discrepancies reported by the inbound crew were corrected during a turnaround inspection and by 0930 that morning the aircraft was ready for the return flight to Seattle. The crew assigned to Flight 100, Captain Lawrence F. Currie, Copilot Lyle O. Edwards, and Stewardess Elizabeth Goods, arrived at operations and made the normal routine preparations for the flight. The pilots discussed the flight with the station agent and all necessary flight papers were completed. Weather for the route was given to the pilots. The weight and balance were determined and both were well within allowable limits. The aircraft was serviced with 2,380 gallons of fuel. The following IFR flight plan was filed with Fairbanks ARTC (Air Route Traffic Control): Alaska 100, a DC-4, departing 10,000 feet Amber 2 Snag, 12,000 Blue 79 Haines, 10,000 Blue 79 Annette, 9,500 direct Port Hardy, 10,000 Amber 1 Seattle; airspeed 185; estimating 7 hours, 44 minutes en route; proposing 0955. At 0940 the two passengers and crew boarded the aircraft. Takeoff was made in VFR weather conditions at 0958. Shortly thereafter Fairbanks center called N 90449 and relayed the ATC clearance, approving the flight plan as filed. The weather conditions at Fairbanks and en route were forecast to be generally good and the flight proceeded in the clear as planned, making routine position reports as it progressed. At 1240, when over Haines, Alaska, at 12,000 feet, Flight 100 canceled its instrument flight plan and informed ARTC that they would proceed VFR to Annette and would file DVFR 2 (Defense Visual Flight Rule) after Annette and before entering the CADIZ (Canadian Air Defense Identification Zone). Thereafter the flight proceeded, reporting its position as DVFR at 1,000 feet. The flight was observed at Patricia Bay, British Columbia, at an estimated 3,000 feet m. s. l. by a tower operator. It was also observed leaving the CADIZ. At 1717 the Alaska Airlines Seattle dispatch office received the following position report by radio from Flight 100: "Dungeness at 16 VFR estimating Seattle at 34." This was the last contact with the flight, which crashed shortly thereafter. All five occupants were killed. N 90449 crashed in heavily timbered mountainous terrain March 2 and was not located until March 3, 1957. The crash occurred approximately in the center of the "on course" zone of the northwest leg of the Seattle low frequency radio range, about 11 nautical miles southeast of the Dungeness fan marker. This leg of the Seattle range defines the center of Amber Airway 1 between the Dungeness intersection and the range station. The minimum instrument en route altitude for this segment is 5,000 feet. Because of adverse weather and inaccessibility of the location, CAB investigators were unable to reach the scene until March 6. The investigators noted that the wreckage had been disturbed prior to their arrival; some components were missing, presumably carried away by persons unknown. The path of the aircraft during the final seconds of flight was clearly defined in the heavy timber growing on the steep slope against the aircraft smashed. The aircraft’s first contact with the trees was at a point 650 feet from the wreckage. From this point it cut a level swath on a heading of 106 degrees magnetic, the width of its wing span, into the steeply rising wooded slope at an elevation of approximately 1,500 feet m. s. l. The terrain immediately ahead of the aircraft‘s path rose to an altitude of 2,000. 2,100 feet MSL.

Probable cause:

The Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was a navigational error and poor judgment exhibited by the pilot in entering an overcast in a mountainous area at a dangerously low altitude. The following findings were reported:

- No malfunction or emergency existed and the aircraft was intact prior to its initial contact with the mountain,

- Several errors and omissions in the course of the flight Indicate the crew was lax and not giving proper attention to their duties,

- A navigational error resulted in the aircraft being three to four miles west of the flight path assumed by the crew,

- The pilot flew into instrument weather without obtaining a proper clearance,

- The aircraft crashed in terrain obscured by clouds.

- No malfunction or emergency existed and the aircraft was intact prior to its initial contact with the mountain,

- Several errors and omissions in the course of the flight Indicate the crew was lax and not giving proper attention to their duties,

- A navigational error resulted in the aircraft being three to four miles west of the flight path assumed by the crew,

- The pilot flew into instrument weather without obtaining a proper clearance,

- The aircraft crashed in terrain obscured by clouds.

Final Report: