Crash of a Cessna 414 Chancellor in Enstone

Date & Time:

Jun 26, 2018 at 1320 LT

Registration:

N414FZ

Survivors:

Yes

Schedule:

Enstone – Dunkeswell

MSN:

414-0175

YOM:

1971

Crew on board:

1

Crew fatalities:

Pax on board:

1

Pax fatalities:

Other fatalities:

Total fatalities:

0

Captain / Total hours on type:

9.00

Circumstances:

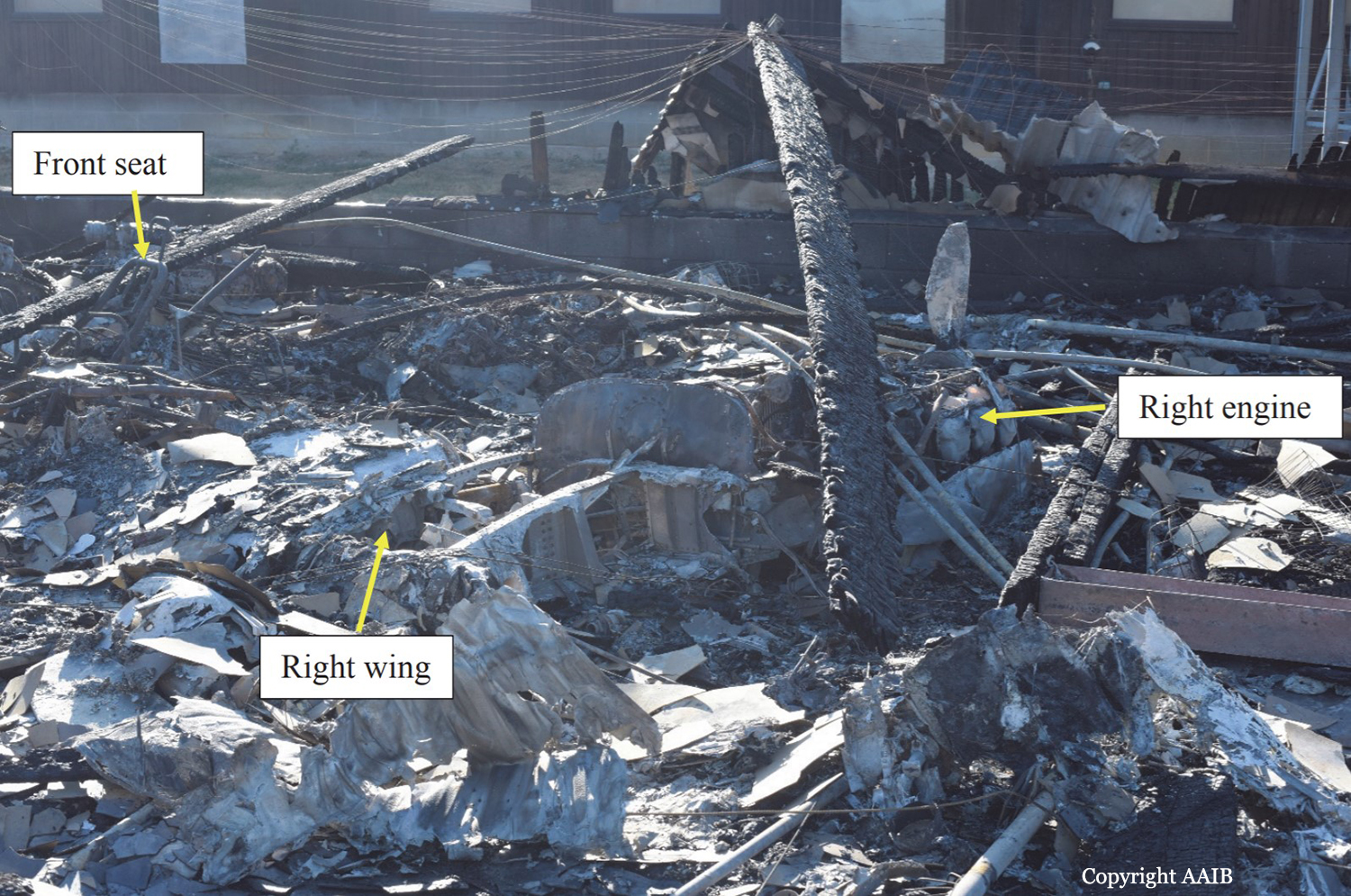

The aircraft departed Dunkeswell Airfield on the morning of the accident for a flight to Retford (Gamston) Airfield with three passengers on board, two of whom held flying licences. The passengers all reported that the flight was uneventful and after spending an hour on the ground the aircraft departed with two passengers for Enstone Airfield. This flight was also flown without incident.The pilot reported that before departing Enstone he visually checked the level in the aircraft fuel tanks and there was 390 ltr (103 US gal) on board, approximately half of which was in the wingtip fuel tanks. After spending approximately one hour on the ground the pilot was heard to carry out his power checks before taxiing to the threshold of Runway 08 for a flight back to Dunkeswell with one passenger onboard). During the takeoff run the left engine was heard to stop and the aircraft veered to the left as it came to a halt. The pilot later recalled that he had seen birds in the climbout area and this was a factor in the abandoned takeoff. The aircraft was then seen to taxi to an area outside the Oxfordshire Sport Flying Club, where the pilot attempted to start the left engine, during which time the right engine also stopped. The right engine was restarted, and several attempts appeared to have been made to start the left engine, which spluttered into life before stopping again. Eventually the left engine started, blowing out clouds of white and black smoke. After the left engine was running smoothly the pilot was seen to taxi to the threshold for Runway 08. The takeoff run sounded normal and the landing gear was seen to retract at a height of approximately 200 ft agl. The climbout was captured on a video recording taken by an individual standing next to the disused runway, approximately 400 m to the south of Runway 08. The aircraft was initially captured while it was making a climbing turn to the right and after 10 seconds the wings levelled, the aircraft descended and disappeared behind a tree line. After a further 5 seconds the aircraft came into view flying west over buildings to the east of the disused runway at a low height, in a slightly nose-high attitude. The right propeller appeared to be rotating slowly, there was some left rudder applied and the aircraft was yawed to the right. The left engine could be heard running at a high rpm and the landing gear was in the extended position. The aircraft appeared to be in a gentle right turn and was last observed flying in a north-west direction. The video then cut away from the aircraft for a further 25 seconds and when it returned there was a plume of smoke coming from buildings to the north of the runway. The pilot reported that the engine had lost power during a right climbing turn during the departure. He recovered the aircraft to level flight and selected the ‘right fuel booster’ pump (auxiliary pump) and the engine recovered power. He decided to return to Enstone and when he was abeam the threshold for Runway 08 the right engine stopped. He feathered the propeller on the right engine and noted that the single-engine performance was insufficient to climb or manoeuvre and, therefore, he selected a ploughed field to the north of Enstone for a forced landing. During the approach the pilot noticed that the left engine would only produce “approximately 57%” of maximum power, with the result that he could not make the field and crashed into some farm buildings. There was an immediate fire following the accident and the pilot and passenger both escaped from the wreckage through the rear cabin door. The pilot sustained minor burns. The passenger, who was taken to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, sustained burns to his body, a fractured vertebra, impact injuries to his chest and lacerations to his head.

Probable cause:

The pilot and the passengers reported that both engines operated satisfactory on the two flights prior to the accident flight. No problems were identified with the engines during the maintenance activity carried out 25 and 5 flying hours prior to the accident and the engine power checks carried out at the start of the flight were also satisfactory. It is therefore unlikely that there was a fault on both engines which would have caused the left engine to stop during the aborted takeoff and the right engine to stop during the initial climb. The aircraft was last refuelled at Dunkeswell Airfield and had successfully undertaken two flights prior to the accident flight. There had been no reports to indicate that the fuel at Dunkeswell had been contaminated; therefore, fuel contamination was unlikely to have been the cause. The pilot reported that there was sufficient fuel onboard the aircraft to complete the flight, which was evident by the intense fire in the poultry farm, most probably caused by the fuel from the ruptured aircraft fuel tanks. With sufficient fuel onboard for the aircraft to complete the flight, the most likely cause of the left engine stopping during the aborted takeoff, and the right engine stopping during the accident flight, was a disruption in the fuel supply between the fuel tanks and engine fuel control units. The reason for this disruption could not be established but it is noted that the fuel system in this design is more complex than in many light twin-engine aircraft. The AAIB calculated the single-engine climb performance during the accident flight using the performance curves3 for engines not equipped with the RAM modification. It was a hot day and the aircraft was operating at 280 lb below its maximum takeoff weight. Assuming the landing gear and flaps were retracted, the engine cowls on the right engine were closed and the aircraft was flown at 101 kt, then the single-engine climb performance would have been 250 ft/min. However, the circumstances of the loss of power at low altitude would have been challenging and, shortly before the accident, the aircraft was seen flying with the landing gear extended and the right engine still windmilling. These factors would have adversely affected the single-engine performance and might explain why the pilot was no longer able to maintain height.

Final Report: