Circumstances:

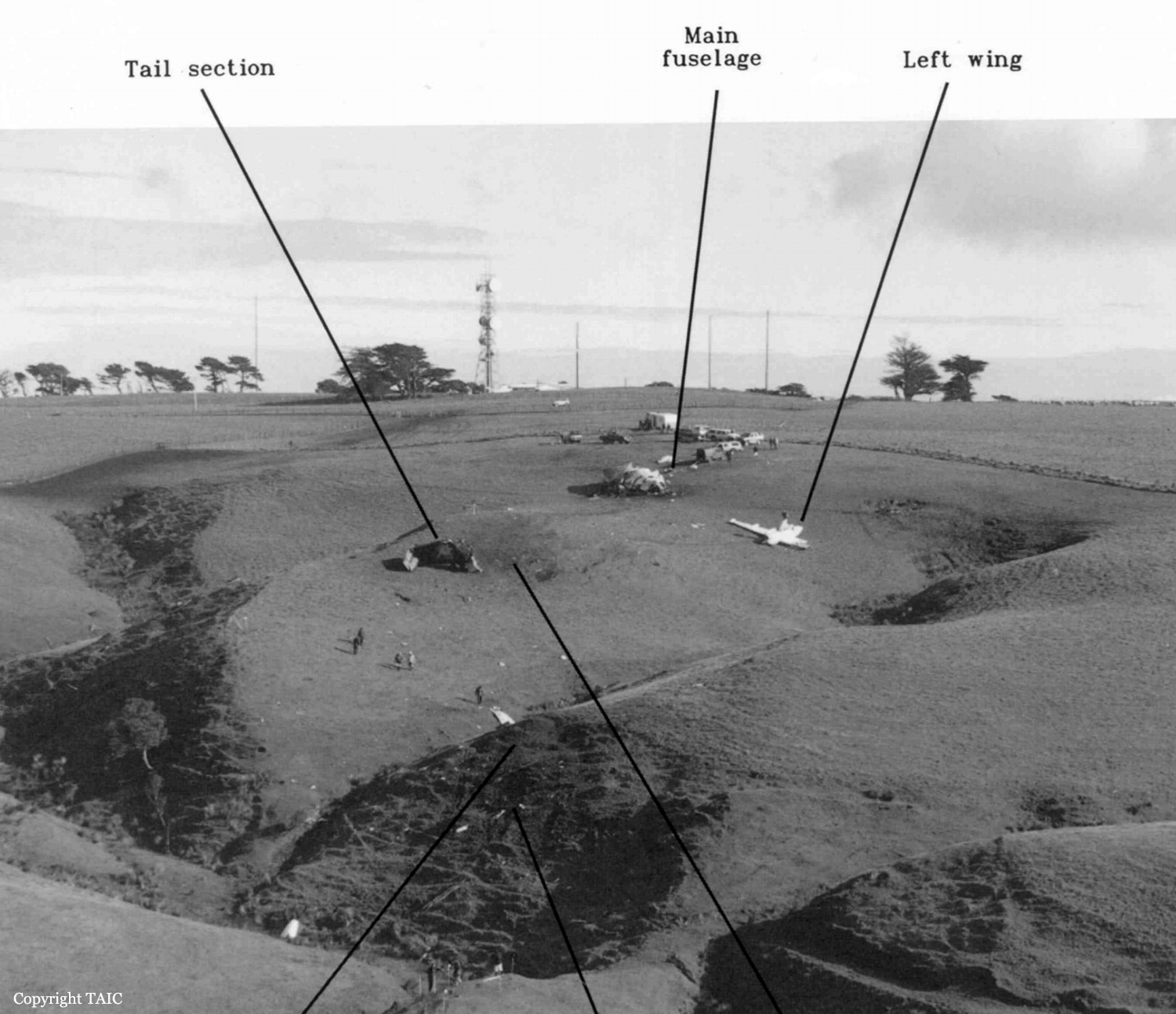

The crew requested engine start at 2128 and Post 23 taxied for runway 23R at about 2132. The flight data recorder (FDR) showed that during the taxi a left turn through about 320° was made in 17 seconds. Post 23 departed at about 2136 with the first officer (FO) the pilot flying (PF). The planned cruise level was flight level (FL) 180 but the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) showed that in order to get above turbulence encountered at that level the crew requested, and were cleared by air traffic control (ATC), to cruise at FL220. The autopilot was engaged for the climb and cruise. There were 2 CVR references to the crew’s use of the de-icing system to remove trace or light icing from the wings. CVR comments also indicated that stars were visible, and that the aircraft’s weather radar was serviceable. At 2159 ATC cleared Post 23 to track from near New Plymouth very high frequency (VHF) omni-directional radio range (VOR) direct to Tory VOR at the northeast end of the Marlborough Sounds, and at 2206 ATC transferred Post 23 to Christchurch Control. The CVR recorded normal crew interaction and aircraft operation, except that climb power remained set for about 15 minutes after reaching cruise level in order to make up some of the delay caused by the late departure. At about 2212:28, after power was reduced to a cruise setting and the cruise checks had been completed, the captain said, “We’ll just open the crossflow again…sit on left ball and trim it accordingly”. The only aircraft component referred to as “crossflow”, and operable by a flight deck switch or control, was the fuel crossflow valve between the left and right wing tanks. The captain repeated the instruction 5 times in a period of 19 seconds, by telling the FO to, “Step on the left pedal, and just trim it to take the pressure off” and “Get the ball out to the right as far as you can …and just trim it”. The FO sought confirmation of the procedure and said, “I was being a bit cautious” to which the captain replied, “Don’t be cautious mate, it’ll do it good”. Nine seconds later the FO asked, “How’s that?”. The Captain replied, “That’s good – should come right – hopefully it’s coming right.” There was no other comment at any time from either pilot about the success or otherwise of the fuel transfer. During this time, the repeated aural alert of automatic horizontal stabiliser movement sounded for a period of 27 seconds, as the stabiliser re-trimmed the aircraft as it slowed from the higher speed reached during cruise at climb power. Forty-seven seconds after opening the crossflow, the captain said, “Doesn’t like that one mate… you’d better grab it.” Within one second there was the aural alert “Bank angle”, followed by a chime tone, probably the selected altitude deviation warning. Both pilots exclaimed surprise. After a further 23 seconds the captain asked the FO to confirm that the autopilot was off, but it was unclear from the CVR whether the captain had taken control of the aircraft at that point. The FO confirmed that the autopilot was off just before the recording ended at 2213:41. The bank angle alert was heard a total of 7 times on the CVR before the end of the recording. During the last 25 seconds of radar data recorded by ATC, Post 23 lost 2000 ft altitude and the track turned left through more than 180°. Radar data from Post 23 ceased at 2213:45 when the aircraft was descending through FL199 about 1700 metres (m) southeast of the accident area. Commencing at 2213:58, the ATC controller called Post 23 three times, without response. He then initiated the uncertainty phase of search and rescue for the flight. The operator had a flight-following system that displayed the same ATC radar data from Airways Corporation of New Zealand (ACNZ). The operator’s dispatcher noticed that the data for Post 23 had ceased and, after discussing this with ACNZ, he advised the operator’s management. There were many witnesses to the accident who reported noticing a very loud and unusual noise. Some, familiar with the sound of aircraft cruising overhead on the New Plymouth – Wellington air route, thought the noise was an aircraft engine but described it as “high-revving” or “roaring”. Witnesses A were located about 3 kilometres (km) south of the southernmost part of the track of Post 23 as recorded by ATC radar, and about 6 km south of the accident site. They described going outside to identify the cause of an intense noise. As they looked northeast and upwards about 45°, they saw an orange-yellow light descending through broken cloud layers at high speed. A “big burst” and 3 or 4 separate fireballs were observed “just above the horizon” about 5 km away. No explosion was heard. The biggest fireball lasted the longest time and was above the others. The night was dark and it had been drizzling. Witness B, almost 7 km to the northeast of the accident site, observed light and dark cloud patterns moving towards the northwest. She thought the moon caused the light variation; however moonrise was almost 3 hours later. This witness also first observed a fireball below the cloud at an elevation of about 6°. She described it as “a big bright circle” followed by 2 smaller fireballs that fell slowly. No explosion was heard. Witness C, who was less than 1000 m from the aircraft’s diving flight path, described seeing the nose section falling after an explosion “like a real big ball of fire”. The wings were then seen falling after a smaller fireball that was followed by a third small fireball. The witness said it was a still night, with no rain at that time, and the fireballs were observed below the lowest cloud. The fireballs illuminated falling wreckage and cargo. Witness D, also less than 1000 m from the accident site, described parts of the aircraft falling, illuminated by the fireball. Witnesses generally agreed that the first and biggest fireball was round and orange, and then shrank away. Descriptions of the smaller fireballs varied, but were usually of a more persistent, streaming flame that fell very steeply or straight down. A large number of emergency service members and onlookers converged on the accident area. Those who got within about 1000 m of the scene reported a strong smell of fuel. The first item of wreckage was located at about 2315. The main wreckage field was on hilly farmland 7 km northeast of Stratford at an elevation of approximately 700 ft.

Probable cause:

Findings are listed in order of development and not in order of priority.

- The flight crew was appropriately licensed and rated for the aircraft, and qualified for the flight.

- The captain was experienced on the type and the operation, and approved as a line training captain, while the FO was recently trained and not very experienced on the type.

- The aircraft had a valid Certificate of Airworthiness and records indicated that it had been maintained in accordance with its airworthiness requirements. There were no relevant deferred

maintenance items prior to dispatch of the accident flight.

- Although the aircraft had been refuelled in one tank only, it probably took off with the fuel balanced within limits.

- Some fuel imbalance led the captain to decide to carry out further fuel balancing while the aircraft was in cruising flight.

- The captain’s instructions to the FO while carrying out fuel balancing resulted in the aircraft being flown at a large sideslip angle by the use of the rudder trim control while the autopilot was engaged.

- The FO’s reluctance to challenge the captain’s instruction may have been due to his inexperience and underdeveloped CRM skills.

- The autopilot probably disengaged automatically because a servo reached its torque limit, allowing the aircraft to roll and dive abruptly as a result of the applied rudder trim.

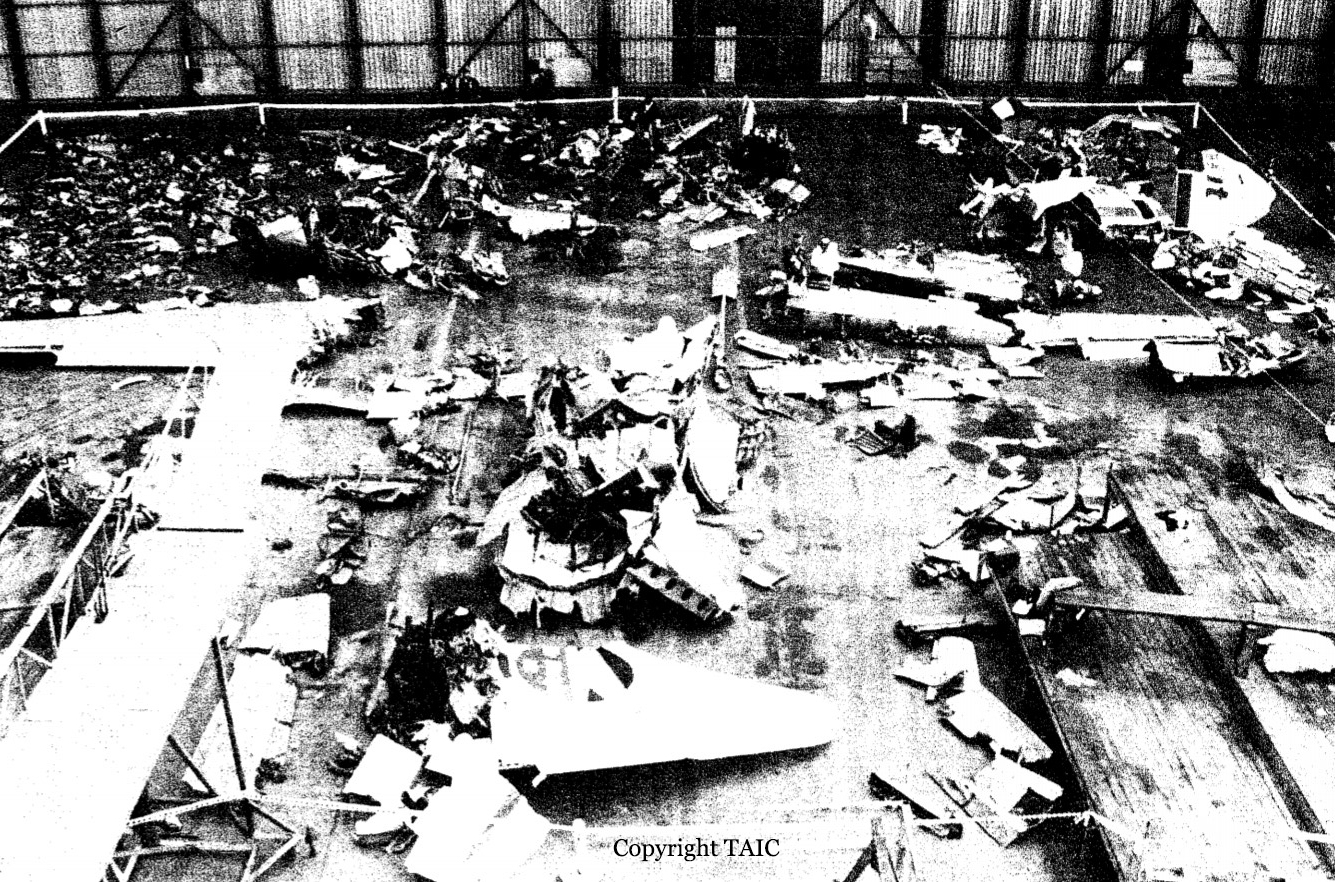

- The crew was unable to recover control from the ensuing spiral dive before airspeed and g limits were grossly exceeded, resulting in the structural failure and in-flight break-up of the aircraft.

- The in-flight fire which occurred was a result of the break-up, and not a precursor to it.

- The applied rudder trim probably contributed to the crew’s inability to recover control of the aircraft.

- The crew’s other control inputs to recover from the spiral dive were not optimal, and contributed to the structural failure of the aircraft.

- The flying conditions of a dark night with cloud cover below probably hindered the crew’s early perception of the developing upset.

- The AFM limitation on use of the autopilot above 20 000 ft should have led to the crew disconnecting it when climbing the aircraft above that altitude.

- The crew’s non-observance of this autopilot limitation probably did not affect its performance, or its automatic disengagement.

- If the aircraft had been manually flown during the fuel-balancing manoeuvre, the upset would probably have not occurred.

- The operator should detail the in-flight fuel balancing procedure as a written SOP for its Metro aircraft operation.

- The AFM for the SA 226/227 family of aircraft should include a limitation and warning that the autopilot must be disconnected while in-flight fuel balancing is done, and should include a procedure for in-flight fuel balancing.